Over the years of your writing activities, you have compiled a list of words you have promised yourself not to use at the beginning of a sentence. A prime candidate for non-use is the word “one.”

Sometimes, when you begin an essay or a review or a blog investigation, the word “one” comes to you and you find yourself thrust into thinking such tropes as “One of the major features of…” or perhaps “One quality every memorable story contains…” or, this: “One day, you were thinking…”

Another word on your do-not-use list is “it.” Imagine all the times you have done so, begun a sentence with ‘it.” No; it is too painful. You have in your time, without serious thought, begun innumerable sentences with the Dickensian “It was…” or your own variation, “It is…” as in, It is a matter of some concern, or It is a truth universally recognized…

The one-two combination of your literary agent and the editor, Renni Browne (of Self-Editing for Fiction Writers fame) has put yet another word on your do-not-use list as a sentence opener—“as.” Your agent, who was editorial director at one time of two rather big houses, is, no surprise, a shrewd editor. You listen to her. She has certainly opened publication and editing doors for you. Renni Browne has provided you a generous blurb for your most recent book. You listen to her; you do not begin sentences with “as.”

You work to avoid beginning sentences, in particular first sentences in stories, chapters, or paragraphs, with gerunds, such as “Having awakened later than planned that morning, Fred rushed through his shower and shave, ate no breakfast, and shorted his dog’s usual walk.”

Of course there are other “starters,” such as “because,” which has nearly the same effect as “as,” not to forget “until.” You come hard wired with dislike of the word “that” in any sentence, sometimes taking unwarranted excursions in syntax to avoid it, and when you factor in your agent’s distaste for adverbs with your own, the thought of beginning a sentence with an adverb of the “-ly” class causes you to quiver.

In recent months, you have also considered adding “with” to your list: “With no pervious warning…” or “With no prior thought…”

Small wonder you sometimes have difficulty getting a workflow started. All these restrictions wrest you from your more interior “vision” of a narrative line, the place where idea, emotion, and, often, metaphor collide, producing a narrator who is inside the material, dealing with it from within rather than observing it with wry or amused detachment from without.

The conflict here is with your notion that early drafts, in particular the first draft, should be got down with as little thought as possible. Early thought is the equivalent of a traffic guard when school is not in session, an unnecessary focus on words and usage rather than ideas, feelings, implications, and those wonderful associations that come seemingly without thought, as though they’d been there all the time, waiting to come out, your own squeeze at the metaphorical toothpaste tube of dramatic vision.

These words are prologue to the fact of your participation this morning in a three-hour presentation on the short story at the Ojai (CA) Word Fest, wherein you had twenty-five individuals in a class room, attempting to convey to them things you believed they needed to know in order to write short fiction that stands any chance of being published in today’s turbulent publishing climate.

For starters, you guess the median age of the group to be close to sixty. You have some delightful experience with this age group. You also have experience with other demographics, including undergraduate level, graduate level, and so-called reentry individuals, men and women in the workforce, wishing to enhance their education. Each group radiates with a different personality force.

While you were interacting, discussing, demonstrating, and suggesting with today’s group, you were impressed with the number of want-to-be writers who were so happy to hear your own confessions of being baffled by certain techniques, concerned by their lack of reading background, struggling to maintain the voice that was authentically theirs.

Fearful of the potential for creating a plodding hundred eighty minutes of the session, you set forth an ambitious tour through the minefields of short story and the things you see as of absolute significance to the art of producing it.

By that act, you learned something you probably knew all through your years in the teaching trenches, nevertheless, you say it here to have gone through the process of writing it.

Lecture and information are like story in that the best way to approach is with too much information, which you attempt to fit into a small cup. None of the media, lecture, information, or story, is in the final analysis, about fact or mere data; they are about feelings and emotional impressions. Anything other causes them to fall into categories of propaganda, sermon, screed/rant.

Most important of all, allow the audience to see how bafflement and bewilderment are a part of the process; they contribute to the final effect every bit as much as the preparation, the pruning, and honing down.

Perfection is not for the writer, nor is it for the individual who attempts to make sense of life, the process which produces the tools and mechanics of story. We strive not for perfection but rather a higher, more nuanced level of bewilderment.

We often need to begin with lists of words we dismiss out of hand because they are too opaque and cumbersome to provide the dazzling clarity of the chaos, bewilderment, and uncertainty in which we were created and in which we live, striving for answers.

Saturday, March 31, 2012

The Toothpaste Tube as Metaphor

Friday, March 30, 2012

Failure

The verb and noun associated with failure are the equivalent of the tails given youngsters before the start of Pin the Tail on the Donkey. They represent missed connections, missed opportunities, performances so off-target that they produce the laughter of derision as their reward rather than the candy bar or cheap toy given as a prize for the one player coming closest to anatomical reality.

The entire scenario of Pin the Tail on the Donkey can be argued to be a mass exercise in which young persons are inoculated against exposure to risk or to risk’s cousin, accident. Such games inject the worm of potential humiliation into play. Winners are seen as those being closest to the norm. Losers are, in effect, scolded into refocusing their vision of what is and what is not correct.

Failure often brings with it the added burden of having disappointed someone or some religious, social, or philosophical ideal. A typical example of such early stages of failure is the failure to share which, because it speaks to one of the great tenets of the social contract, is rated in severity several degrees higher than failure to turn out the lights or to do one’s assigned social chores.

Another early type of failure is the failure to prepare in advance for some requirement, something as quotidian as doing one’s homework, say, or the more egregious failure to prepare for an examination. From such failures, we learn valuable lessons about planning for future events.

How difficult it is to remember that exquisite moment when your failure was more of a disappointment to you than to any code of behavior or the disappointment you may have caused one or more individuals. To say you had few or no failures as you raced from your early years into your twenties and thirties would betray a serious vacation you’d taken from Reality without acquiring souvenirs or touristy tee shirts. Your failures, sometimes epic, were in degree of attitude, in control of maintaining yourself as a functioning organism. There were some near misses where grades were concerned, some c minuses; even a D when it seemed to you that geometry was forever out of your reach. There was the one F of which you were actually proud, ROTC.

Your hope in writing about failure in general and that specific moment where you understood how much you cared and how your own performance was at least the equal of others involved will in time provide you with the memory of the event, as so many of the things you have written about herein bring the sharp etch of recall.

You do recall one circumstance in your thirties, and in your first editor in chief circumstance, where your lack of attention to production cost details on a particular title produced the landscape for a financial disaster. You approached the publisher with the information, well before the fact, and with it a list of possible solutions, including scrapping the project.

“Well, well,” the publisher told you. “You’ve made your first big mistake. You must give back all your bonuses for your good results, take an immediate pay cut, and suffer a demotion.” Then she smiled. “I did not hire you for parts of you, but for the whole person. Get your ass back to work.”

The publisher decided to go forth with the work, which ultimately earned out. No profit to speak of, but no loss, and a reasonably worthwhile project.

Nearly ten years later, in another publishing house, you’d made an error in judgment of an author and of an executive member of the publishing team. This time, no finances were involved. You believed you had an effective strategy to employ. When you presented the publisher with the data, he expressed his disappointment in you, three times, all the while you attempting to draw his attention to your memo of subsequent strategy.

When he expressed his disappointment in you the fourth time running, you observed that the publishing house had scant room for a victim, and he was taking the entire room. Your resignation was on his desk the next day.

Through some inherent lack, whether of interest, insight, or a combination of the two, you fail to see the extensive admiration of and appreciation for Samuel Beckett. There are, for you, a number of his works, in particular the prose narratives, alive with a resonance, insightfulness, and steadfast deliberation. In equal measure, there are some of his works that have left you with no sense of having been occupied. Nevertheless his presence is indelible with you for his mantra about failure. Fail again, but fail better.

Failure is not the goad to you that it has become to so many you read and hear about. Perhaps this is because you see nothing extraordinary about it. Perhaps this is because you see the notion of perfection as being more hype than shimmering reality. Perhaps your algebraic and geometric deficiencies obtain in your failure to see a connection with successful execution and perfection.

Failure is merely not doing something as well as you’d have liked, given your feelings invested in it. Thus feelings trump failure, and thus you will surely try again in support of your feelings, whether this is story related, relationship related, or understanding related.

You will not reread Beckett for the stature of having “gotten” him, whatever that may mean, but for the respect to someone for whom the work mattered to the point where he tried to wrest a living language from it, a language that could carry for sentences and paragraphs and entire scenes the load he placed upon it.

Failure is every bit as much a part of life as death is. When an individual dies, we do not say of her, she failed at life; instead, we recall all the wonders she provided for the persons, animals, and plants she cared for. We say of her, she succeeded in living a life that transferred the pleasures of being alive. And then we say of her that she died, but we neither say nor think she failed. We maybe aware of some project she failed to complete or some goal she failed to reach, but we rate her as we rate ourselves, aware for a time, perhaps even aware of abilities or strengths for a time, aware of having a finite amount of energy to which these abilities and strengths maybe put.

What does failure mean to you?

Failure means not having got it, whatever it maybe—including life, itself—right, but don’t go away. Not yet.

Thursday, March 29, 2012

The Desk as Landscape for Adventure

Your goal of a neat, orderly desktop is victim to the active part of you, depositing, piling, forgetting an assortment of things difficult to classify.

Every Monday, Lupe, the maid, seems to have an inkling of your desire for order and classification. She not only dusts and cleans the desktop, she suggests in her arrangement of things possibilities for neatness you have never considered.

By Monday evening, your presence has made itself known again, a cautionary tale, reminding you of a sad truth: if it is too neat, it is too serious.

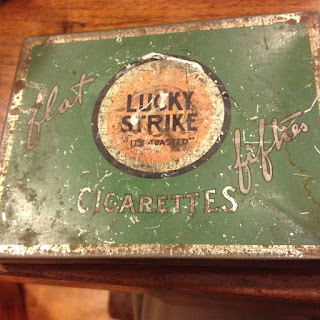

From your literary agent, the gift of two packets of Harney & Sons Hot Cinnamon Spice Tea, and a particular treasure, the party favor put at your place at the recent birthday celebration for a dear chum.

To be sure, there are any number of reading glasses purchased at various drugstores, often in the belief that you’d lost all in your possession. There are note pads, three-by-five index cards, a tin of cinnamon mints, and a tin from a German manufacturer of fountain pens.

If you look closely at the photo of the wind-up robot party favor, which has some remarkable built-in quality that causes it to stop and change directions rather than plummet off the edge of the desk, you will see the bottom portion of an iPod Touch, which is, after all, in the toy class, which is at the heart of this essay.

No question about it, you have not outgrown a fondness for toys and things which may not be toys but nevertheless exude a toy-like confidence. This also applies to the Big Little Books on the ledge of the kitchen window looking out upon the grand next-door garden.

No question about it, you have not outgrown a fondness for toys and things which may not be toys but nevertheless exude a toy-like confidence. This also applies to the Big Little Books on the ledge of the kitchen window looking out upon the grand next-door garden.Before romance with women, there was romance with toys, with the treasures to be found inboxes of Cracker-Jacks, such candies as the taffy Guess-What, cereal boxes, and those remarkable toys—Little Orphan Annie decoder ring—you got by sending proof of purchase of Ovaltine to some remote P.O.Box, then the agonizing wait until what you were sure would be the most remarkable thing ever would appear one day in a rumpled envelope, addressed to you.

These treasures informed such imagination as you had. They were nearly as remarkable as books with their power to adventurous worlds well beyond your present scope. With such toys and something so simple as a raincoat, you were The Shadow or The Green Hornet. Better still, you were your own invention, disguised as a small boy with round, horn-rimmed glasses.

The accouterments of a writer or editor or professor are nothing in comparison to the tool kit of an emerging boy, who would settle for nothing les than adventure and, when there was none to be had, when there were no chums with whom to rouse up these adventures, there were the protagonists and antagonists (you did not know them by those terms) of books read to keep your sense of danger and mystery alive.

The iPod mentioned earlier and its mate, the iPhone, as well as some Italian and English fountain pens are grown-up toys. The penknife you carry is excellent for opening a letter, cutting a string, rendering in sections the Super Deluxe Submarine Sandwich from the Italian Deli on De La Guerra and Laguna, but the pocket knife you carried as a boy was more business-like. Adventures were riskier then, or so it seemed then.

Being a long-time devotee of the adventures of Dick Tracy, you are alert to the prescience of some of his gadgetry, some of which is with you as an iPhone with applications for music, picture taking, two flashlights, a QR scanner, a conventional scanner, a magnifying glass, and other such Swiss-Army-like applications, all of which make you more fit for the world about you.

At one point in your earlier years, your sister asked you for a favor; you were to accompany her to the toy department of a five and dime on Wilshire Boulevard, where you would pick things she’d planned to give the brother of her great girlfriend. Since you knew the brother, you’d be a reliable index of things. You were even to be paid for your services with a wind-up car of your choice. You were in heaven then, browsing the toy counter at Woolworth as though it contained secrets of the universe. There was one toy in particular that could not have cost more than twenty-five cents, but how wonderful it was. A steep slide down which a tiny car ran, gathering speed to track through the loop at the end of the slide. You tested it several times to make sure it fulfilled its promise. If Gordon did not appreciate this, he was no longer worth knowing.

A week later, you saw Gordon at school. When you asked him how he liked the death-defying car and other birthday presents, he punched your arm and told you his birthday was not for six months.

On the way home from school, your arm still hurt from where he’d punched you, but you were smiling to yourself because your birthday was next week and you knew your sister had set you up from a perfect understanding of her little brother.

Thus not only fond memories but the title for this venture: The Desk as a Landscape for Adventure.

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Attend Your Inner Salon

When thoughts or conversations turn toward the salon as a gathering place for creative sorts, you become of a conflicted state, recalling on one hand the frequent written accounts of them with envy, and contrasting your own real-time experiences with them.

At an early juncture in your friendship, one of your great pals set a salon in motion, causing a cascade of events that would, you both realized later, make a recipe for a text on how to write a comic skit. Surely the venue had something to do with the calamitous results, Beverly Hills being in many ways the incarnation of the Emerald city of Oz.

The first indication that anything had gone amiss was when, at about ten o’clock, a screenwriter threw a drink at a novelist. In those days, Democrats and Republicans seemed to blend socially, at least to the point where, if alcohol were being served, politics would not be discussed. Not half an hour after the first drink being cast, a cup of punch went from the right hand of a Democrat onto the shirtfront and face of a Republican.

By eleven, an actress demanded to be taken home, her dudgeon having exploded into a string of epithets directed at an assistant director. But the question of who should take the actress home raised added stress, bordering on the areas of sexual tension, resulting in cross words between a film editor, a television story editor, and a first husband.

You have, in more recent years, experienced salons where the sexual tensions were less pronounced and, in one notable case, the most significant argument came amongst proponents of Romano cheese and advocates for Parmesan. Much more civilized. And perhaps, not unlike the maturation process relative to cheese and wine, your own maturation process had inched forward a notch or two.

On your way home from your most recent salon, still comfortable with the after effects of rascally red wines, a splendid salad Nicoise, and some cheese puffs topped with caramelized onions, you couldn’t help indulging the conceit of the university teacher’s old standby, the compare-and-contrast essay, which also happens to be a sturdy companion of the writer. Thinking back to the more memorable of your salon experiences, you pulled the outstanding characters forth.

There, on your kitchen shelf, was a well-corked quarter-bottle of zinfandel. The refrigerator yielded some Camembert, and the care package thrust upon you by the hostess included a goodly slab of cibiatta. Your kitchen table held forth a ripe Anjou pear. Back to the fridge again for some pitted Greek olives.

In the dim light of the kitchen, you sat peering into the extensive garden next door. A sip of zinfandel here, an olive there, a tug of bread, a slice of pear, and you were comfortably conflating your salons into one literally and figuratively of your own making.

Surprise is an important element to you. On numerous occasions within these blog notes as well as in class notes devoted to the investigation of narrative technique, you’ve made the point that revision for you includes going over and recasting a work in progress until it leads you to a surprise, some discovery that will ratify previously held beliefs or prejudices or, perhaps, show you a new way to hold a tool you’d thought you already knew how to hold.

At about two thirty, after checking to make sure Sally had enough water, then leaving a smear of Camembert on her snack dish, you moved off to bed, comfortable with the surprise that had come from your own, inner salon.

You have not nor do not enjoy or wish for friends some of the individuals you have met at salons. Some are boring or at least of neutral chemistry in your estimation. Others appear too filled with self and the resulting self-congratulation, to the point of self-parody. Yet others are polar to you in ways you have no interest in exploring. These, and others like them, are of a piece with the demographic you discover in the warp and weft of your daily life.

The disagreeable characters you meet in your inner salon are, to a man and woman and child, quite remarkable. One in particular had politics that brought you to the point of wanting to douse her with zinfandel. Some of these do not return the favor of finding you remarkable, even though you are, in realistic terms, their creator. They keep you honest, reminding you that even in your imagination, you are a witness.

They do not have to like you, nor you them, but you do need not to stack the deck against them, either with your choice of words in which you depict them or your failure to listen to them.

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

Home Is Where the Internet Lies

In the ordinary scheme of things, finding a new home is not an easy business. You happened to have been at the right place, which was Craig’s List, at the right time, which was half an hour before leaving to accept a dinner invitation with the individual who has become the academic equivalent of your boss at the university.

409 E. Sola Street was not home when you first entered its premises on January 1, 2011, but in a matter of minutes, you began to see possibilities to the point where you reached for your check book.

Barring any calamity or strange enhancement of fortunes, 409 E. Sola Street will remain your home in the residential sense, on into the indefinite future.

Due to a series of calamities and enhanced good fortune, you are now ensconced in yet another home, a literary home. The calamities have to do with your most recent book by Write Works Press and the enhanced good fortune of it being acquired and reprinted by Water Street Press. The tenancy there has already begun.

Toward the third week in April, a new, enhanced edition of TFLC will appear bearing the Water Street Press logo. At about February of 2013, your collected short stories will appear as Love Will Make You Drink and Gamble, Stay Out Late at Night. In March or April, the project you’re working on now, solo, as your esteemed collaborator struggles for breaths in the hospice at Albuquerque, will emerge as The Dramatic Genome: The DNA of Story.

You’ve a verbal handshake on yet another work of nonfiction, audaciously titled Studies in Classic American Literature, vol. II. The audacity comes from the fact of volume I having been written by D. H. Lawrence. You have been in over-your-head circumstances before, romantically, financially, and literarily. Your version may fall flatter than a botched soufflé, but at least it will be done.

Then back to fiction, two suspense-type misadventures set here in Santa Barbara, one in an upmarket retirement home, the other the funky, south-of-State-Street neighborhood within walking distance from 409 East Sola Street.

These last two are things your agent wishes to reserve for the time being. Water Street Press may continue to be home for these as well, emphasizing on your part a shift from the brick-and-mortar publishing ventures of your earlier efforts into the growing tidal wave of the future of publishing.

As you were coming up in publishing, both as writer and editor, book publishers were called trade publishers, and one of the major reference books was called The American Book Trade Directory. Your first serious job in publishing was with a start-up. You were thrilled to see the company being included in The American Book Trade Directory. You were equally thrilled by the first appearance of a review in Publishers’ Weekly. At the time, all book publishers were called houses. If someone asked if you worked for a book publisher, you corrected them by mentioning your affiliation with a publishing house. Such were the snobberies of the time.

With the exception of the ill managed and equally ill-fated Write Works Press, all your connections and associations were with brick-and-mortar ventures, meaning there was some office somewhere in which grown men and women plied the publishing trade.

Your home at Water Street Press is viral. The executive editor lives and works from Healdsburg, deep within the California wine country. Others of the staff reside in San Francisco. At the moment, publicity and promotion starts in Ojai, within Ventura County, connects over conference calls, emails, and IMs. Promotional materials will go viral when the Water Street web site springs beyond its beta version announcement of better things to come.

You have hitched your literary wagon to a viral star.

Home does not stop there; it reaches to the lion’s head logo at the top page of your own blog site. Lowenkopf. Lion. Head.

The concept took shape, then grew from the editor wondering if you’d be interested in editing a promising package of stories from a promising writer, one that had already achieved a blurb from a major novelist and short story writer.

The conversation subsequently grew to a line of books to be published with the Water Street Press, plus the addition of the lion’s head logo: A Lion’s Head Book, selected and edited by you.

Home was never like this.

Four books a year.

Start looking.

Monday, March 26, 2012

You Call This Conversation?

Well before you began to nourish the idea that there might be fun to be had in reviewing books, when you were in a landscape where you were required to read certain books, whether you enjoyed them or not, when you were at a stage in life where you either liked or did not like a particular book without understanding all the reasons that went with your feelings, the process of selecting a new book to read bordered on the traumatic.

You can recall browsing news stands, used bookstores, and libraries for upward of two hours, sometimes returning home with no selection. Part of this picky approach was because of the unspoken belief that there was somewhere in the world a single book that would serve the transformative purpose of forging you into the writer you envisioned yourself becoming. Although this notion was clearly in the realm of hoping for some miracle, its saving grace was the verb tense, becoming. The transformation would not be an immediate transformation.

While you had notions of wishing as well to become a better student than you were, you included in your vision quest a book that would help you reach the state of a closer reader, one who could extract the methods, theories, and intentions resting slightly below the surface of books you were required to read and comment on as well as in such books you shared some resonant frequency with.

How fortunate you came to your senses, realizing as you did that such books were in effect Maltese falcons, chimeras, literary equivalents of Ponzi schemes. Such books did not exist except in the abstract or your own abstractions. If you wished to heft such books in your hands, you would have to be their author.

Through this slow evolution of process, although you still cast about for reading material with increasing levels of frustration (there were many, many books, but not enough to suit your tastes) you still believed in the powers of reading to forge connections and guide you through whatever age you required being guided through.

A crumb of wisdom, landing on your shirtfront, where, indeed, too many crumbs of brioche and croissants also land, allowed you the additional awareness that the quickest way to find books of interest to you was for you to be engaged in writing something of interest to you.

In so many ways, this has come to form the balance of an equation in which reading and writing are linked to conversation.

Earlier this morning, while you were at breakfast in one of your frequent haunts, the Café Luna, your pen flying over your usual lined note pad, taking down dictation, as it were, of an approach to the presentation you are to give this Saturday at the Ojai Word fest. You were enjoying the approach that began appearing, causing you to warm to it. A writer whom you find unreadable and in general unreasonably full of himself, plunked himself down in the chair opposite you with questions and observations about what you were doing. This was the second time within a week you’d had such a confrontation with him. This time you dispatched him with borderline rudeness, a considerable uptick from your earlier encounter with him.

This behavior had little to do with him interrupting you at work; that happens all the time. The culprit was your interpretation of his it’s-all-about-me type of conversation.

You relish interesting conversation. Your two closest friends are masters of it. Your late wife was brilliant at it to the point where, when the two of you were conversing in public, you were often interrupted by strangers who, hearing you, were moved to join in.

In many ways, you chose your friends for the facility of their conversation, avoiding where ever possible individuals whose interest appears to be playing and replaying scenarios in which they have cast themselves in the starring role to the point where the exchange is more of a testimonial than a conversation.

Disclosure time: you are well capable of inane or mundane, What up, doc? Conversations. You know this about yourself. You are also, to use a metaphor, somewhat of a short fuse when it comes to the likes of individuals such as the unreadable writer this morning, of students in writing classes who are unwilling to listen, who have no mechanism for listening, or who use the “But it really happened that way” approach as a justification for why a thing must be kept as they have written it, no suggestions allowed, tolerated, or countenanced.

That said, you come to the conclusion here in which the difficulties of finding something apt and particular to read may be linked to the pleasures to be had from a discussion that bends your thought and creative processes to a more imaginative angle.

You must put forth considerable effort at having significant conversation with yourself, which is to say you must edit, hone, and otherwise enhance your interior monologue, avoiding inane and mundane conversation with yourself, watching that you do not bombard yourself with cliché or patent untruths or rumors.

Writing and conversing require attention and respect to the process to, among other things, prevent you from keeping it all about you, to prevent you from trying to promote yourself or fantasy banquets honoring you. This is the first in a series of steps that will you to write things of genuine interest to you and to carry forth conversation of genuine interest to others, whereby you may gain to some measure that great reward, surprise.

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Power

An early, bookmarked memory in your experiential hard drive focuses on you at age seven or eight, at play with a group of now forgotten playmates on Cochran Avenue, a long north-south street cutting through residential areas in west central Los Angeles. You are summoned to come inside by your mother, not unkindly but in a tone several notches above supper is ready.

The “inside” to which you were summoned is a lower-floor apartment at 442 S. Cochran, its front room windows opening toward the street, thus the sounds of your play could be heard from within. The reason for the summons was to inform you of an infraction you’d committed. You’d called one of your playmates a name your mother found objectionable.

From the perspective of today’s retrospect moving you south about a hundred miles and into the past by decades, you are relieved to recount that the name bore no racial or even class/social attack.

“But mom,” you protested. “James Cagney called someone a dirty rat.” You were still young for most nuance, thus your mother’s reminder that James Cagney was portraying a character in a film, that he probably did not consider the other character a dirty rat in their personal life any more than you truly believed your playmate was so despicable. You were, she said, caught up in the heat of the moment, and you were being called in to remind you how easy it is to say things in the heat of the moment that have only passing intent. This was already too much for you to take in; you wanted to be back out at play, this incident behind you.

And soon, the incident was behind you; whoever the dirty rat was, he had morphed into something less generic and more likely a specific reenactment of a particular character in a particular story known among your friends and you. Possibly the Green Hornet, Jungle Jim, Mandrake, the Magician; possibly even the Lone Ranger, Terry (of Terry and the Pirates), or The Shadow.

The incident was behind you but, clearly, not the memory—or the implications you have built into its meaning for you; it is much more fraught with meaning now, perhaps well beyond your mother’s original intent. This +perhaps” takes you out of prologue and into the topic point here.

Early on, we have parents as authority figures, then teachers. Then come employers, all of whom exert a certain degree of power. There is much to be said about our choice of friends and romantic partners, where the coin of power is often exchanged, giving the individual some practice with the use of power as contrasted to the designated follower.

Those who become parents take on the ranking system of power. Those of us who enter military service or become medical interns, then residents, or law enforcement or, as you have done, academia. Lecturer. Instructor. Associate, then assistant, then full professor. And publishing: associate editor. Editor. Senior editor. Editor in chief.

Rankings. Positions of power. Invisible insignia on sleeve or shoulder.

Ah, you nearly forgot. Lover. What delightful and fluid movements of power, this person who, with scarcely a thought, causes you to redefine your sense of self into someone who sometimes is at pains to throw power to the winds in order to get an hour or two at his writing, but who now, because of love, is tossing life preservers, guide ropes, any supportive devices to the side for that dizzying sense of what has happened to him because of love.

In the culture where you live, there are no dukes or earls, no lieutenants nor captains. Rather the sense of the possibility of power that comes from following your discipline, living in it as you can to the point where so much is now muscle memory. To teach and edit that, you must reflect on the process, try to identify it, even as it grows within.

So much of the growth process is about risk, and so much of the risk process is affected by love, whether that love is for the process itself, for humanity as a category, or for some special one who inspires you, intentionally or not on her part, to take that leap of risk.

Are you some sort of Bernie Madoff, leveraging power and muscle memory, building on some well-tested paradigm? Or perhaps you have evolved to the point where risk appears to you personified, reminding you of the Wile E. Coyote downward spiral that inheres in taking no risk at all.

I have never slept with a man your age, she says.

Neither, you say, have I.

Saturday, March 24, 2012

Got Conflict?

When you enter the terrain of your own fiction, more often than not, you are dealing with some abstraction of conflicts and issues based on conflicts and what you consider to be moral infractions that you’d experienced yourself, fantasized about, or invented in that limbo crucible between fantasy and imagination.

Next step is to build the participants, which is to say the characters who will demonstrate these abstractions and issues. If and when you are successful in bringing the work to draft form and, eventually, to a satisfactory fruition, you are often given the gift of seeing yourself as you in some similar situation, having learned from the entire experience in ways that may now allow you to cope with similar situations in reality.

If and when you are successful, you are frequently so because of some accidental discovery, some detail that strikes you as having remarkable cosmic significance, even though there are in fact few things related to people that are significant in that sense. This evening, you may have discovered the kind of surprise a character in one of your short stories might well discover. While you were looking for a particular container of detergent you remember having placed in the cabinet under the sink, you came across a 32-fluid-ounce container of a product called Cat Odor Eliminator. You have no memory of having purchased it; you have no need of it. You’ve about completed your fifteenth month here with no memory of having brought the product from your previous digs, much less can you recall purchasing the product nor, indeed, can you think of any time in recent history when you’d had provocation to notice cat odor.

You have no cats. There was a time when you had cats, but not in recent memory. The probable answer to the quasi-enigma is the maid, Lupe, who frequently brings things in, presumably for her use here. Although she does from time to time leave you a Post-it note to remind you to bring home laundry soap or Glade, or Pine-sol, or trash bags, she has never left you a note advising the need for cat odor eliminator.

Lupe often brings flowers or fruit. She has brought you a cut-glass vase and an embroidered pillow. Now there is high probability she has brought you cat odor eliminator, which may eliminate things beyond the ken of your bachelor disinterest, but in this case your bachelor disinterest has become curious.

Perhaps you will one day learn. Perhaps one day, in some proper context, one of your characters will learn, or wonder, or relate the appearance of Simple Solution Cat Odor Eliminator to some cosmic relevance. On such things, story is hinged, devices, compounds, and concepts in orbit about one or more characters, satellites of the fates, if you will.

Another matter destined to become orbital is resident in an event or set of circumstances that took place at dinner this evening, having some relevance to your observations of last night. Under normal circumstances, you do not recall similar things in these notes, at least not on successive entries, fearful that by doing so, these notes will become diary-like rather than their intended notes for development, re-visitation, and self-understanding.

Last night you were fearful of having your head turned by an excess of esteem from your publisher. Tonight, you were at dinner with her and your literary agent, whereupon they both became quite voluble about the kind of writer you are and their esteem. You have been in a more or less similar circumstance with your mother and sister. Although you were not thinking about this at the restaurant, you are thinking about it now, in a way thanking both mother and sister and now agent and publisher for the awareness of the need to take the regard for a moment or two, enough to enjoy it, then move on.

You did, in a sense leaving the two ladies in heated exchange in the parking lot.

Only now, perhaps an hour and a half after the event, thinking what a remarkable opportunity has been handed you for a story which should have as its fulcrum your own dynamic equation of the unthinkable come to pass. You first gave enough thought to this dynamic after reading a novel by the English novelist, Kingsley Amis, called The Green Man, in which the protagonist, Maurice Allingham, an ironic near alcoholic inn keeper, becomes obsessed with the notion of a sexual threesome involving his wife and a bar maid. His stratagem works all too well; Allingham’s wife and the barmaid become some excited by one another that they completely ignore him.

You began looking for other such moments in your reading, finding them with some regularity to the point where you began thinking this was one of the key elements you needed to introduce to your stories. This was not something you could pre-arrange. It must come from the circumstances and energy of the story.

At least two of your stories have such moments, one tangential, the other an actual payoff way of ending the story. In one, a man seeking to adopt a cat at animal shelter is denied the cat of his choice because he is not seen as a cat person. Seething with impatience, he visits a pet shop, only to have the clerk wonder aloud if he would be more satisfied with a nice dog.

The other has to do with a man who is himself under a certain amount of emotional stress, becoming caught up in a romance with a woman who is afflicted with a quirky tendency toward shoplifting.

Get ready for a writer who finds himself sandwiched between publisher and agent.

This is not to say you are uncomfortable being admired—particularly not when it seems to serve up a concept for a story.

Friday, March 23, 2012

Culture Shock

Culture shock is a term applied in appropriate enough directness to the sense of disorientation an individual from one culture feels when immersed in another culture with perhaps differing languages but certainly with different coding in the language the newcomer hears and of the gap in nuance between behavior individuals from differing cultures.

Culture shock can well occur in a city of any size, wherein an individual from one neighborhood strays into another neighborhood. It can happen in mixed company, where responses to a joke are wildly disparate. It can happen when an employee of a large company is sent to headquarters for a meeting or managerial training.

Your own culture shock of a particular and specific nature begin toward the end of 2010, when your agent asked to meet you for coffee because she had a matter to discuss with you.

The matter was the fact of two distinct bites on your six-hundred-twenty-page manuscript, which you’d given the title The Fiction Writers’ Tool Kit. Your agent had two firm offers, the first from a source you’d rather expected, one of the so-called Big Six, a heritage publisher. The second offer had better be pretty good to be worth listening to, you thought as you listened to the details.

The second offer was from a start-up venture, non-brick-and-mortar and, thus, without the overhead or business plan of the Big Sixer. The Acquisitions editor of the new company was a friend of your agent from other times, other publishing industry jobs. Your agent had, in fact, not thought to send this editor your manuscript. The thing that impressed your agent and you was that the editor had pestered her to see it, had looked you up, had read your work, had heard you at a writers’ conference, had decided after reading the preface of your work that she wanted it.

There was no longer any doubt where you would go.

You have seen too many examples of book projects becoming list in the maelstrom of crisis management among the Big Six. And so you made your choice, which led you to one of the most intelligent editorial experiences you have ever had, resulting in a treatment unlike any you’d had previously, all because the acquisitions editor wanted your work.

Your book was out and circulating for three months when the publishing venture exploded, your editor left, secured capital for what is now Water Street Publishing. You followed her and in short order, your book will reappear, phoenix from the ashes, in yet larger format.

Your editor is now your publisher. You are working on another title due in November. A collection of your stories will appear from her in February of 13. Because she had come to Santa Barbara to tape some interviews with you and other of her authors, you met in person for the first time. As of last night, you have a verbal on the other nonfiction project you want to write and as well, she is interested in the two thrillers you have under way.

The culture shock comes from your relative comfort in dealing with editors and your understanding of where you fit into the publishing sphere; you are an acquired taste. You are, thus, well aware of being an outsider even though you are somewhat an insider when you wear your editorial hat. You are used to being regarded as an outsider, a writer whose work is read, sometimes grudgingly, because you have some measure of credentials. You are not used to some of the things your editor-publisher has said about you; they cause you discomfort. This is in its way quite a good thing. It is one thing for you to hope you are of a level, then strive for it with each new project. It is another for you to think you have earned the esteem before finishing the project.

Pure and simple, this is the occasion of the culture shock. Your best hope is the number of times you have told students and clients of the need to get used to the fact that each new project means having to learn to write that project from scratch elements. You cannot take the calculus you learned from Project A to Project B and have it work out to be anything but a derivative of Project A.

While you were leaving your editor after an impromptu—and splendid—dinner prepared by your agent, she walked you to your car, asking you to think in addition to your writing projects about editing. An imprint, she said.

Culture shock.

You spent the early years hoping and dreaming, dashing in a frenzied tango from project to project, reading anything you could get your hands on, thinking all manner of outrageous and magical incantation, winnowing, borrowing, experimenting, to have reached this point, where thought and incantation are the least things you need to do, culture shock put out of your mind, the words plucked from the cosmos and splashed down on the note pad of screen, so that the work, the real work, may begin.

Thursday, March 22, 2012

Friendly Fire

Among the many aspects and traits it has become fashionable to endow upon a character, fatal, psychical, and emotional flaws rank high. Thus we have front-rank characters with autism, Tourette’s syndrome, stuttering, the Capgrass Syndrome, cancer, sexual issues, fear of heights, and a veritable smorgasbord of afflictions, prejudices, and predilections of enough severity to insure some dramatic deviation of behavior from the norm.

Who among us would relish reading about the solution of a complex mystery by a normal individual? Who among us would go so far as to fantasy a romantic relationship with an opposite member bearing the emotional equivalent of 20/20 eyesight? The ability to see twenty feet away with normal clarity is so—so ordinary. So normal.

Which of us yearns to read a drama set in an historical era where there was no war, no famine, no rebellion, no shortage of men or women, no epidemic?

You suppose it possible to argue that expectations, in reality and in story, can be classified as a character flaw of some egregious rank. Because of their use in inflammatory domestic situations, expectations have been moved variously to the back of the bus or entirely off the bus. “I expected better of you.” “I was expecting a raise.” I was expecting -- and Don’t expect—(fill in the blanks as you prefer) are shots fired across the bow of the enemy ship; they are provocateurs, instigations, challenges.

In life as in story, individuals who arrive bearing expectations turn out to be troublesome, picky guests, exuding the kind of aura a room-freshener spray cannot overcome.

Although we may try to keep our expectations to a healthy minimum (no one has figured how minimal “healthy” is) in life, it is more often than not amusing to see grown adults in a situation, attempting to portray a Buddhist-like detachment when they are, in fact, tuned in to some outcome in some part of the earth or other that will have consequences for them.

Those of us who send straw persons into scenes and narratives are well aware of the impact investing those straw people with expectations can produce. You could say—and sometimes do—that there is a direct relationship between the number of expectations a straw person has in a given story and the emergence of that straw person into a vital, memorable character.

Conventional wisdom may be personified here to argue with conviction how nothing lives up to its expectations, which are always better or worse. Through a strange and curious turn of logic, you argue yourself into camping with the Optimists; things (events, people, books, music, meals) tend to work out much better than you’d expected. True, your judgment is rendered after the fact of you having looked with some distaste at the event before the fact of your engagement with it; nevertheless, Optimism often overcomes pessimism for you, thus you find yourself with expectations of being if not deliriously happy, then of relative good cheer, exhibiting all the energy that accompanies good cheer.

Any given story you work on produces within you a replica of that twisted logic informing Optimism. You do not expect a story to work out as well as you’d hoped when you were first attracted by its signal fires and you’d then set forth to track it down, see if anything were wrong, if there were anything you might do to help.

After a draft or two with a relatively flat or so-what ending, you expect to discover through another great gift to the composer, surprise, a less-than-flat-ending. Past experience has taught you to keep at the material until the surprise arrives, often with a greater emotional clang than the original vision for the story. Pausing now as you compose this, you are seeing a procession of such endings, all of which came from what seemed a great emotional distance, light, you might say, from a distant star.

You are much attracted to noir writing, stories that seem to emerge because individuals had no expectations and subsequently became thrown into situations where they began to have them, only to shut them down in the belief that they were too good to be true and thus, why subject themselves to yet another bitter disappointment?

There are times when you find it easy to confound the equations of Optimism and Pessimism as the only possible paths a narrative can take. From your political beliefs, you distrust if not resent attempts to make a middle-of-the-road approach seem sane, healthy, possible; these arguments seem to you deliberate attempts to propagandize, to detract from and make fun of your position.

All positions, yours among them, are of equal absurdity. Expecting that to be the general case whether in Reality or story, you see them all—however nuanced these positions may be—as targets. Not as enemies. As targets. And so you take aim. Thus do you open the field of vision for your own position to be struck by, shall you call it friendly fire?

You expect, after some drafts, the cavalry to arrive, bagpipes droning—a surprise discovery, the revelation that causes the warring sides to look up for a moment or two before returning to their squabble.

You expect surprise. You expect to have to wait for it to arrive. When it does present itself, you have that final judgment to make: was it better surprise or less than you expected?

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

Close Quarters

Story is the cramped room of dramatic narrative, the shared bed of insomniacs, the literary equivalent of sharing a bedroom wall with a loud snorer. Life and story share the understanding that life is not fair, that there is any justice involved in deciding whether your airplane seat is next to an individual of enormous girth, or if the baby of the couple in back of you loses its lunch on you rather than them.

In recent years, story has become the loud neighborhood party, reaching its crescendo at three in the morning, so far as historical, speculative, and informative exposition are concerned.

If there were enough room for characters to relax, spread out, get comfortable within a dramatic landscape, then kindness, consideration, and civilized conversations would result, leading to an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century vision of accord, which was often boring enough then, without these stabilizing events being brought to the present.

Story thrives on close quarters, sprung sofas, chilly foyers, steamy atria, carpets with disappointing patterns, despicable room service, cranky concierges. Thus tempers flare, best-laid schemes fizzle, and in sudden bursts of irrational impatience, hidden agendas are unintentionally revealed. Serious individuals become unconsciously funny and pedants are given to self-satire.

Comfort zones and rest areas are nice concepts for inter- and intrastate highways. If they appear in story, they signal the reader that the story is rushing toward being over.

You may well lead a reader to suspect some impending surprise or reversal, but you do even better, having raised such expectations, to present a surprise or set of expectations of—how shall you say this?—of surprising areas well beyond the readers’ expectations.

How do you accomplish such expectation and surprise? You begin by bringing forth some venture that emerges as a surprise to you. After all is said and done, you have an idea of what the characters suspect and you know what will surprise you if not them, and so you move ahead with plans to surprise yourself?

How do you surprise yourself?

You begin by signing a power of attorney by which authority you allot your characters and imagination for a specific length of time. If your characters see you taking such steps, they may wish to hide, at which point you’ll have to arrange for plausible behavior that may be seen taking place at moments most inconvenient and fraught.

Story may reflect an atmosphere of convivial good cheer and brotherhood, all gone or on its way to hell. Individuals within a story may attempt to demonstrate to you their appreciation for your recognition of their contribution. Say nothing; allow them to nourish these feelings; story flourishes in direct proportion to the degree and intensity of story in progress.

Story serves to monitor the literary equivalents of fire alarms, paying close attention to anything that assures safety and accord. If it is comfortable, you need to rough it up; if a thing seems likely in a positive sense, that thing, at best, can be a red herring, a signal that awful and awfully funny things await.

Funny things await; they sometimes overtake us and allow us to remain unaware they were there at all much less there and funny. True sadness is the prospect and event of missing out on fun when it was there all the time. The possibility of it being either love or insanity exists when no fun is present, yet you behave as though there were.

Characters who stand out in their jobs are those who believe this is not the time to be funny; you never have trouble portraying them or allowing them to rack up their own bills for wanton destruction. In similar fashion, characters who crack up over something everyone around them considers serious are also worth hanging onto. And watch out for characters who, up until now, seem to have got everything they’ve wanted without much in the way of effort. They are headed for the big scene, the one of near Wagnerian consequence.

If there is ever any doubt that your characters are having too much fun, getting along too well, able to cope in convincing fashion with their environment, you need to bring them around fast,

The reader does not at anytime wish to see a sign in your text: NO CHARACTERS WERE INJURED DURING THE WRITING OR SUBSEQUENT REVISIONS OF THIS STORY.

If you are to remain awake, neither do you.

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

True Brit: The DNA of Digby Wolfe

“Beginnings are easy,” Digby Wolfe told you as you set out to collaborate on a novel. “You set a character down on a rope stretched across a chasm. Then you begin handing things to the character. Endings are the hard part.”

He was right. We got our characters out on to the rope within a matter of a paragraph, loading them and ourselves with things.

You sometimes look at those pages with amazement; the collaboration was as though each of you was trying to outdo the other with complications that were weighted down with moral, political, and romantic innuendo.

Anytime you worked together, it was an attempt to fit wildly diverse styles together, you skittering on, him wondering if we’d really needed that comma six pages back. “Don’t you think that slows the effect?” And you to reply, “I thought we’d dealt with that.”

“Yes, but don’t you see—“

Of the classes you taught together, some were apt to observe, “It was like watching a ping pong game on steroids.” At which point, he would observe, “You should have known better than to take steroids before coming to class.” And you would wonder, “Are we giving them anything?” and he would respond, “We’re giving them us.”

At one point, after what seemed a particularly energetic semester, with students soaring off to publications or performances, he approached you, shaking his head. “I don’t see how we’re going to do this. We’re both thin. One of us has to be Laurel, the other Hardy.”

You thought, girth to the contrary notwithstanding, you were more Hardy than Laurel, but he would not hear of it, even in the abstract of his vision of how we should approach our joint classes.

Individuals you never thought you’d meet—all of whom you’d met because of him--were wont to tell you how you had no idea what it was like to work with Digby. Walter Matthau for instance, or Jonathan Winters, or Richard Pryor, or John Denver, or Budd Schulberg, or Frank Whatzisname. “He always thinks he’s right,” they’d say, and of course you’d say, “except when he’s not constructing story.”

You’d had this mini-conversation so often and in so many different settings; it informed at long last your own vision of what story is: Two or more persons arrive in a scene, each believing he or she is right.

Not all that long ago, you were at a small dinner party, celebrating the forthcoming birthday of a great friend, the only other, in fact, on the same plateau with Digby. Sufficiently fed and wined, you were pleased when the host, a venerable fixture from NBC TV news days, announced he was sending us all home before we became too maudlin and began making embarrassing speeches, but he did want to close with the observation that of all the people he’s known, our birthday boy was the one who could be seen as the modern equivalent of a Renaissance Man.

This tribute was fitting.

As you were driving home, you were thinking then, as you do now, that Digby Wolfe is also of that rare breed. An actor, a songwriter, a stand-up comic, a playwright. You recall his stories of being the opening act for the young, up-coming group, The Beatles. You know how it was he’d come to “invent” the television phenomenon, “Laugh-In.”

You knew when it was time to get him out of L.A. and the concept of Hollywood, and the reality of his Emmy Awards, into the more mysterious reality of academia, first at USC, where he was, for a time, your student, until, in an ironic flip, you became collaborators for the first time. And discovered in subsequent years the unfolding of a friendship that was as filled with surprise and revelation as you’d known in a friendship.

The result? Once again, Digby Wolfe is right: Endings are difficult. As you write this, he is in intensive care at a hospital in Albuquerque, his prognosis is an ending and, because it is related to lungs, a difficult ending. What was thought to be pneumonia has revealed itself to be cancer. You have had enough experience with cancer to know that cancer in the lung area does not take kindly to second seasons, particularly when the star has had a few second seasons already.

Breath does not come easily to him now. Your farewells had to filtered through Patricia, his wife. You told him you’d finish the book you’d begun one afternoon over steaming bowls of pasta with clams and conversation. “Wait,” he’d said. “Go back a bit. What was that you just said?”

You’d spoken of looking for a dramatic genome that contained the DNA of story.

“That’s our title,” he said. “Are you in?”

You told Pat to tell him you’d finish it for both of you, sooner now, without him going back to question commas. You told Pat to tell him that if there were such a thing as an afterlife, he’d bloody well get his British arse to the book signing, and not to plan on wearing the suit he and Anthony Newley co-owned back in the London days.

Even though death presents itself about being for the dying, it is ever so much more for the living, a reminder to do so many things, to remember, to care, to be outrageous, to watch one’s dreams closely for cameo appearances.

What you brought to the writing table before you noticed that bright, articulate Brit sitting toward the rear of your Novel Beginnings class at USC, you expanded exponentially after that night you found out who he was and cemented a relationship over an imaginative pasta combination involving smoked salmon, green peas, onions, and a fruity olive oil.

Working on The Dramatic Genome: The DNA of Story, you will have more than your notes and his drafts. You will have him asking you to go back for a look at something you might have missed, and of course the thing you are most likely to have missed is him.

Monday, March 19, 2012

Wring out the Old, Wring in the New

For the past few years, a recurring theme in your thoughts is the running-on-empty meme. As the theme did in fact recur, you began to associate it with the fear of running out of material, whatever that happened to mean, and the greater fear of becoming repetitious and, even worse, derivative, all in the interests of meeting self-imposed blog post deadlines.

Happy to say, these thoughts did not last long; there always seemed to be something you wished to investigate or consider or both, possibly there’d be things you found worthy of development after the investigation or consideration produced the next plateau.

As the time progressed, you began to see that you’d gained a vast appreciation for the feeling of running on empty because, with its own resident tingle, there was also the sense of adventure of what would come when you began the day finding yourself confronted with a blank screen or blank sheet on a note pad.

The goal for some time was being in the state of mid-project. With something under way, how could there be any problem setting to work tomorrow or, for that matter, the next day.

The potential for knowing what you’d be working on often had you sitting to work with a word already in mind, and then the work after that, more or less with no end insight. What comfortable prospects—except that they were not as comfortable in the actual moment as you’d supposed. What if the words were there, and the sentences, too? What good were they without the buzz of excitement or the tingle of anticipation?

Soon after you reached this apparent dead end street, it came to you how comfort was not the companion for whom you had much respect. Too much comfort could lead to moments in which thought could work its way in, perhaps even to the point of awakening the critical functions, and you know what happens when they are awake and yammering for breakfast, yowling judgments at the top of their voices.

Thought equals judgment equals the derailment from the emotional track, which means enthusiasm and a favorite passenger of yours, mischief, have had a chance to escape—an opportunity they always take.

The fear of coming to work with no reserve tank topped off during a decent night’s sleep, is an energizing experience of high order, alerting such mind as you have to watch anything and everything about you for clues and associations with which to form connections.

True enough, you sometimes find yourself trying to hush the inner voice that warns you how dangerously low your resources are and, later, skimming over the sense of relief you felt when there were things to talk about, connections to be made, associations plucked from the cosmos, and sudden, sharp close-ups of cliché tropes to be crossed out.

True enough, the musician practices for manual dexterity and technical agility, but the musician also practices to send the sound of the practiced notes into muscle memory, where they reside beyond thought. True enough, they maybe summoned by a thought, but those are formal in nature and if performed as the result of thought, they are likely to sound colder, more mechanical.

The same is as true of words, cached in the muscle memory equivalent of the writer. No matter if English has more or less synonyms than other languages; all languages have synonym and antonym to some degree and not all story is written in English.

Practice makes words become a part of the inner vocabulary, the writer vocabulary, where in some cases the emotional payoff of a story rests on the difference between ergo and therefore, between I think not and I don’t think so. The writer will have already thought through the fact of English being the only language to use “do” as a kind of shim to level out language. I do think you are angry; as opposed to I think you’re angry. Each has a particular tang to it; the writer must recognize when one is more appropriate than the other or, for that matter, any other.

There is something inherently formal-sounding in well-thought-out narrative. This formal presence causes the words to sound as though being delivered in a valedictory speech at a graduation rather than conversation or interior monologue or daydreaming from a character.

Narrative issuing from the sense of a near-empty tank carries the vocabulary of risk, tension, gasping for air not found in ordinary speech and as such goes with more speed and deliberation to the readers’ viscera, where even in translation it is anything but formal.

You practice not for dexterity or to perfect the timing, but to run out the tank.

Some day, you may in fact be empty of a thing to say, but you will have the panting, gasping, sweating, hand wringing body language to convey it, and story will have survived within you for yet another day.

Sunday, March 18, 2012

Mona Lisa's Mustache (Apologies to Dali)

When you look at photos or paintings of pastoral scenes, you experience an interior sense of calmness, perhaps extending to a feeling of nostalgia for a time when you were at such a place. There was no story present within the scenes, only the artist’s arrangement of landscape, tempered by light and shadow.

If anything, the landscape was so relaxing and peaceful that you found yourself trying to distract the imp of the perverse from awakening with mischief on its mind. Avid readers and habitual writers have come to understand how the relationship between calmness and ordinariness is so close to the destabilizing events we associate with story. A beat or two before it is asked to do so, the mind of the habitual reader wonders when the storm will strike, or the dam will burst, or the fire will erupt.

The detective, after a grueling day devoted to the routines associated with securing witnesses, clues, or the leads necessary to propel a mystery story, settles down, at last to a long overdue supper or, better yet, snugs into the comforts of bed for needed sleep. Again, that mind of the habitual reader begins to work in the form of a question. Where will that next destabilizing event issue from? A good bet is the telephone: A superior officer calls, avid for news of progress in solving the case. Perhaps another version of the call, a subordinate brings forth the news of a new crime, with newer complications.

Used properly, calming scenes, stabilizing scenes, or some dramatization of a return to a non-threatening routine can become the advance guard of first-rate suspense. The reader not only wishes to know, the reader wishes to become suspicious, in the process, quite possibly threatened or intimidated.

This bit of psychology is well demonstrated by the image of a short fuse, only just lighted. The reader will tolerate being manipulated a scant moment longer, but the destabilizing device must soon go off, otherwise all has been for nothing at all because two pieces of comfortable fabric will have been stitched together, causing one overly long narrative blah.

Unless the intent is for a venture in the kind of mystery called the tea cozy, calmness and ordinariness must be mugged with some regularity, extending in as many directions as possible, appearing with the argumentative intensity of plausibility.

In other words, calmness, restorative nice weather, and well-presented agreement and accord, presented in the proper small doses, serve to trigger the pressures, moral judgments, and psychological events the reader has come to expect. You are attempted to repeat this because of its dramatic importance: Too much calmness between earthshattering discovery will bring the story to a screeching halt, at which point the reader is wont to set the book down somewhere, then forget where it has been left.

The right amount of calmness has the reader wanting in metaphoric terms to draw mustaches on the Mona Lisa or spray paint gang graffiti on brick walls. It is in fact your belief that nearly the entire range of graffiti fans are taken by it because it is often imaginative but also because there is a larger market for imaginative graffiti than supposed. Graffiti is more than mere trespass; it is a statement of impatience.

Readers become impatient when there is too much calm, they begin inventing their own mustaches and graffiti if the writer does not do it for them.

Of course pacing is important. Such wildly diverse storytellers as Mark Twain, George Burns, and Jack Benny were as famous for their timing and delivery as they were for the payoff of the story.

No points will be given for merely making things happen; things need to be caused to happen, presented at the crest of the dramatic wave or, to borrow an analogy from jazz and mix the metaphor, to borrow a beat from one measure, then place it in the next.

Telling a story is more than the mere relating of events, one, two, three; it is the shrewd intersperse of delay, threats of impending accent, and the surprise of an accent where it is not expected.

You could say—in fact you do—event in story is not the main feature.

Definitions and Implications

1. Let us begin with definitions:

2. Editing is work, requiring concentration, an awareness of the author’s intent, respect for the author’s intent, and wishing for the author to be as successful and far-reaching as possible with the work at hand.

3. Teaching is work. You wish to convey a range of vision to a wide demographic of student, wanting for as many aspects of the demographic as possible to connect with the vision, then modify it to the point where the vision has the student’s fingerprints all over it.

4. Writing is not work; it is play, but it is difficult play, excruciating play in which, if the play falls short, the entire purpose of the writing may be lost. Play is to childhood as technique and behavior are to adulthood, thus play becomes practice for adulthood and adult games. Play is to writing as writing is to life. Thus writing is life. Although some approach writing from places such as anger or a sense of abandonment or frustration at not being able to control sufficient portions of Reality, there is yet the potential that they will have found ways to use play as a counterpoint or subtext. Henry Miller was such a person, no stranger to play, although he had other agendas. Ayn Rand was no such person. The writing of each individual, seen in relationship to play, speaks with eloquence to this point. At the time you knew Miller, he was able to tell you that a bad day of painting was better than a good day of writing. He offered you your choice of a booklet he’d written about painting (The Waters Reglitterized) or a watercolor. You’d read most of his material at the time. You chose the watercolor, which you still have. Somehow, the books of his you’d had are not with you. This was not a result of overt deliberation. You only met Ayn Rand once, under circumstances where discretion was well advised. You were quite drunk, at the stage of drunkenness of extreme garrulousness and good fellowship. Even at this remove in time, you are pleased with yourself for all the times when you were that drunk and were still shrewd enough a judge of your behavior to know to keep your words and actions at a minimal level. With the exception of an acute sense of disbelief, of you’ve fucking got to be kidding disbelief, you got nothing from Ayn Rand and have nothing to offer in return.

5. With those definitions and observations lodged into place as prologue, you are ready to set forth another belief: To the extent that you can, you attempt to come at the day’s session of writing with a sense of it being enlightened play, in which you intend to play yourself out.

6. You hope you’ve written enough things during the times of your writing life to have used up all the jokes, incidents, and smart-ass remarks you’ve saved up over the course of your life and are thus able to come at whatever it is, even things such as this blog essay, with a few things cached away as possible.

7. The implication of # 6. Supra is that the jokes, incidents, smart-ass remarks, and associations of today are fresh rather than leftovers from previous days.

8. Further implication is that the associations and discoveries you make today are surprises for you, some of them admittedly unhappy ones, nevertheless things you’d not anticipated.

9. When you were young, barely in your teens, you generally fell asleep the moment your head hit the pillow, a circumstance that often came as a disappointment because you’d wanted to have a few moments to review things you’d experienced or had wanted to experience during the day.

10. After a time, the notion came to you that you could prolong your waking in-bed time by inventing stories which, depending on their capacity to interest you, would keep you awake longer, sometimes as much as two hours longer.

11. Story was almost by definition a series of events that kept you awake, avid of information about the outcome or consequences tumbling down from the earlier events.

12. You did not consider it fair to contrive intriguing events during the day that would keep you awake later; the narrative had to begin as you settled into bed. The consequences of not being able to design an intriguing opening situation or problem or adventuresome expedition were simple enough: you lost the game by falling asleep.

13. At some point, you reckon thirteen or fourteen, you began with a more or less ensemble cast of boys, girls, men, women, and, of course, you, as characters. It was not long before you realized sex had come into the calculus and you were on your way to adventures beyond your power to contrive.

14. With the realization that you were beyond your power to contrive, story became the flame and you the moth.

Friday, March 16, 2012

The Disappearing Narrator: an Existential Mystery

In a manner similar to the way the age of a tree may be inferred by counting the rings of its trunk, the age of a particular story may be estimated from the form of narration.

More often than not, the analogy holds: tree ring is to tree age of tree as mode of narration is to story.

Eighteenth--, nineteenth--, and mid-twentieth century narratives are wonderful; you anticipate your continuing discovery in each of these eras previously unread treasures for as long as your ability to read and enjoy endures.

Things as vital as story and its readership continue to grow--evolve, if you will. So do those individuals who produce story move ahead in their growth. Since these blog notes are intended to be seeds, scattered and sewn for your own benefit, you, who are at the moment reading Jane Austen’s Persuasion and a mid-twentieth century mystery novel set in Sicily and originally written in Italian, must, if you are to expect any progress in your written work, examine this phenomenon you have noticed of narrative growth.

You must look for ways and places where it has begun to grow away from what it was and toward what it has now become.

And what, exactly, has the modern novel and short story become that it had not been before?

Let’s begin with Virginia Woolf (1882—1941), although numerous of her contemporaries as well as her predecessors, wrestled with the techniques for depicting a closer, more accelerated demonstration of human consciousness. She achieved this in a number of titles, notable among them To the Lighthouse. The goal among tellers of story, you believe, has always been to find techniques, vocabulary, and conventions of use for portraying in action rather than providing mere descriptions of consciousness and awareness. One reason for this belief is the way, in your opinion, authorial descriptions of such consciousness blunts the reading experience to the point where reading certain canonical works from the past become more a chore than a pleasure.

The reason you have undertaken to place lifespan dates of so many of the writers here is because so many of them were alive and flourishing at more or less the same time.

A notable example of a groundbreaker is George Elliott (1819-88) and her remarkable Middlemarch published in 1872